HAVANA -- Six-foot-two, brown skinned and with semi-curly hair, Denny walked confidently into a government warehouse for a recent job interview. Sitting across from the white manager, he rattled off his qualifications: high school diploma, courses in tourism, hard worker.

They weren't good enough: He needed his white brother-in-law to vouch for him, Denny recalled.

"Black people tend to do everything bad here," the manager said.

After Fidel Castro's revolution triumphed in 1959, he declared that Cuba would be a raceless society, banned separate facilities for blacks and whites and launched a string of free education and health programs for the poor -- most of them blacks.

Many blacks people still support Castro, saying that without him they would still be peons in the sugar cane fields. One black Cuban diplomat said he had no hope of an education, and his grandmother no medical care for her glaucoma, until the revolution came along.

But listen to some blacks, particularly those born after 1959, and the failures of the revolution also become clear.

"Everyone is not equal here," said Ernesto, 37, as he dodged traffic on a Havana street. Tall and athletically built, he once hoped to be a star soccer player. He now gets by selling used clothing, and said he's continually hassled by police just because he's black.

In recent years, a new attitude has been emerging quietly, almost secretly, among Afro-Cubans on what it means to be black in a communist system that maintains ‘‘No hay racismo aquí'' -- there's no racism here -- and tends to brand those who raise the issue of race as enemies of the revolution.

"The absence of the debate on the racial problem already threatens . . . the revolution's social project," wrote Esteban Morales Domínguez, a University of Havana professor who is black, in one of his several little-known papers on race since 2005.

In another paper, he noted that "much of the research that has been done on the subject in general has been put away in drawers, endlessly waiting to be published." Black filmmaker Rigoberto López also broached the sensitive topic in a TV appearance in December, saying that while the revolution had brought about structural changes toward racial equality, "its results do not allow us to affirm that its goals have been achieved in all their dimensions."

'A NEW MOMENTUM'

Afro-Cubans familiar with the situation say black and white Cubans also have been establishing a small but growing number of civil rights-type groups. The government has not cracked down on such usually illegal activities, but neither has it officially recognized them.

"There is a new momentum, which the government is surely frightened by," said Carlos Moore, a Cuban-born expert on race issues now living in Brazil.

In recent years, the Castro government has been on the defensive on the race question. In last year's book 100 Hours With Fidel by French-Spanish journalist Ignacio Ramonet, Castro admitted that while the revolution had brought progress for women and blacks, discrimination endures.

"Blacks do not live in the best homes; they're still . . . performing hard jobs, sometimes less-remunerated jobs, and fewer blacks receive family remittances in foreign currency than their white compatriots," he said.

Still, Castro added: "I am satisfied by what we're doing to discover causes that, if we don't fight them vigorously, tend to prolong alienation in successive generations."

But Castro's own Communist Party and government fall short on the race front. Only four recognizably black faces sit on the party's 21- member Political Bureau, and only two sit on the government's top body, the 39- member Council of Minis- ters.

The highest-ranking black in Cuba is Esteban Lazo, a former party chief in the provinces of Havana and Santiago de Cuba. Lazo was tapped by Castro when he took ill last summer, along with brother Raúl Castro and four others, to help rule Cuba in his absence.

And yet, black faces populate Cuba's political prisons. Some of the nation's best known dissidents are black. They include independent librarian Omar Pernét Hernández, mason Orlando Zapata Tamayo and physician Oscar Elias Biscét. The latter was sentenced to 27 years for, among other things, organizing a seminar on Martin Luther King's non--violent forms of protest.

"Race is the biggest social issue facing Cuba," said Enrique Patterson, a Cuban-born Miami author who writes extensively about race, and calls this nation's race problem a "social bomb."

"If this problem isn't addressed, Cuba will not be governable in the future."

RACE STILL DIVIDES

Patterson said he believes that while Castro has kept the lid on the race issue by squashing past attempts by blacks to organize or speak out, a post-Castro Cuba won't be able to contain the frustrations.

"If the Cuban government were to permit black Cubans to organize and raise their problems before [authorities] . . . totalitarianism would fall," he said.

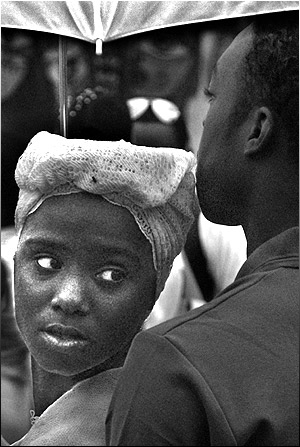

Look beyond the white, brown and black faces in government propaganda murals plastered throughout this island under the slogan Somos Uno -- We Are One -- and race still divides. Today's Cuba is more racially and socially integrated than the United States, but it is far from color-blind.

Whites are clearly preferred in the government controlled and highly profitable tourism industry, from taxi drivers to waitresses and hotel maids. Meanwhile, blacks in Old Havana are continually stopped by police for I.D. checks on suspicion of black market activities.

Television programs overwhelmingly show most blacks in menial jobs, and Cubans, like other Latin Americans, still use a cutting expression for a black they admire: El es negro, pero . . . '' -- He is black, but . . .

"Just look at the cab drivers lined up in Old Havana," Cito, 52, an Afro-Cuban doctor whispered so his neighbors would not overhear his complaint. "You rarely see someone who looks like me."

Nearly three years ago, Cito, fed up with his paltry government salary and what he described as the racist attitude of his white supervisor, left his post. He now makes his living on the black market, buying meat from farmers in the countryside and selling it in Havana.

"This country has taken away all of my will to live in it," said Cito, 52, whose tiny and sparsely furnished apartment seems like a luxury compared with the rest of his crumbling building. Cito, 52, who is dark-skinned and has the body of a linebacker, recalled his early days in medical school when he dated his now ex-wife, who is white.

He recalled a running conversation his future mother-in-law would have with her daughter: "He's not a bad guy. I know his family. But there are a lot of other young men in the school you can date. Why him?"

He knew exactly what she meant; she did not want a black son-in-law.

DISPARITY IN NUMBERS

Cuba's official statistics offer little help on the race issue. The 2002 census, which asked Cubans whether they were white, black or mestizo/mulatto, showed 11 percent of the island's 11.2 million people described themselves as black. The real figure is more like 62 percent, according to the Institute for Cuban and Cuban-American Studies at the University of Miami.

And the published Census figures provide no way at all to compare blacks and whites in categories like salary or educational levels. Ramón Colás, who left Cuba in 2001 and now runs an Afro-Cuba race-relations project in Mississippi, said he once carried out his own telling survey: Five out of every 100 private vehicles he counted in Havana were driven by a Cuban of color.

The disparity between the census' 11 percent and UM's 62 percent also reflects the complicated racial categories in a country where if you look white you are considered white, no matter the genes.

"You know, there are seven different types of blacks in Cuba," said Denny, who now works as a waiter but dreams of a hip-hop career. From darkest to lightest, they are: negro azul, prieto, moreno, mulato, trigueño, jabao and blanconaso.

For Denny, one of six children, the color quagmire astonishes even him sometimes. One sister is married to a light-skinned Cuban who considers himself white, and another is married to a Spaniard. And even though his complexion would allow him to claim something other than black, he says, adamantly and without any reservation, "Me, I am black. I choose to be black."

This identification, he says, was reinforced by his experiences in schools where teachers often favored his lighter-skinned classmates.

"Even though he knew they didn't have the answer," he recalled of one teacher, ‘‘he would rather call on them than ask me."

And while Cubans of his mother's and grandmother's generations readily accept endearing uses of negro or negrito, his peers are treating it as their "N'' word.

"It's unacceptable," said Denny, whose access to the outside world via illegal Internet and satellite TV hook-ups have given him a perspective on race that Cubans in general lack.

He pays for those with U.S. dollars he earns, a relative rarity for blacks. Since whites make up the overwhelming majority of the Cuban exile (population), whites get the bulk of the cash remittances sent to relatives on the island. A study in 2000 by UM's Cuba studies institute found that the average white Cuban received $81 a year in remittances, compared to $31 for non-white Cubans.

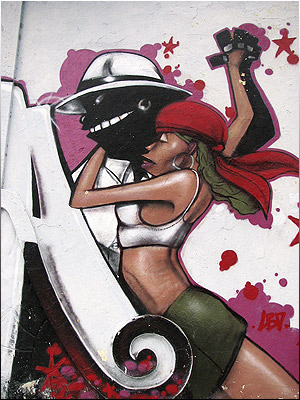

Denny, the would-be hip hop performer, said he also sees racial changes coming through his kind of music, which sometimes defies the government and peppers its rhymes with references to racism.

He remembers one man in particular who landed in jail. ‘‘He was rapping, ‘If you are black, and feel that you are treated equal,' raise your hand. . . . He was arrested by the police."

MOVEMENT

On a recent Sunday at a Havana park, a group of mostly black Cubans in their 20s and 30s, including some dreadlocked Rastafarians, carried on an intense discussion on reggae icon Bob Marley, whose songs depicted the black struggle.

"He understands what we are going through," said Omar, 31, proudly showing off a life-size portrait of Marley tattooed on his back.

Such talk can be scary to Cubans who know their history. While blacks made up a good portion of the mambises who fought against Spanish colonial rule, they remained poor and ill-treated after Cuba won its independence. A black revolt in 1912 was brutally crushed, leaving behind hundreds of dead and a deeply ingrained fear.

"Their rights and protection from potential genocide and violence depended on them never trying to organize politically as blacks," said Mark Sawyer, a UCLA professor who spent 11 months in Cuba researching his recently published book, Racial Politics in Post-Revolutionary Cuba.

That kind of talk also likely scares the Castro government.

"There is an unstated threat," Moore said. "Blacks in Cuba know that whenever you raise race in Cuba, you go to jail. Therefore the struggle in Cuba is different. There cannot be a civil rights movement. You will have instantly 10,000 black people dead."

Yet something of a black movement is indeed growing, he added.

"It's subterranean, and taking place among intellectuals and people in general," said Moore. "The government is frightened to the extent to which it does not understand black Cubans today. You have a new generation of black Cubans who are looking at politics in another way."

But the government still has a hold over black Cubans -- the fear that the collapse of the communist system would make their lives even worse.

"Black Cubans are afraid of a return of the people in Miami," Moore said. "They are afraid of a restoration of the U.S. influence. The last link Castro has to the black population is based on those two fears. The third is: They are afraid that the social advantages the revolution brought in terms of health, education and even political participation will be abolished if American influence and white influence are reestablished."

Denny says he shares those concerns, but is willing to take the risk.

"We are never going to be slaves again," he said. "We are not stupid. We know the development of the world . . . We intend to have a better life."

More information about the Cuba:

The Miami Herald withheld the name of the correspondent who wrote this dispatch, and the last name of most of the people interviewed, because the reporter lacked the Cuban journalist's visa required to work on the island. Miami Herald Translator Renato Pérez contributed to this report.