TELA, Honduras -- The three women in pumpkin-colored skirts, with sand clinging to their naked feet, held maracas over their heads and shook them in rhythm with drumbeats.

Nearby, bare-chested men with colorful headdresses moved with snake-like motions. The men and women then joined for an explosive Baile de Guerra -- a 200-year-old war dance commemorating their ancestors' liberation from English enslavement.

The dancers were Garífuna, descendants of African slaves who were shipwrecked on the Caribbean island of St. Vincent in 1665 and mixed with Carib and Arawak Indians. After clashes with the English, they were sent in 1797 to Honduras, from where they spread to neighboring Nicaragua, Guatemala and Belize.

Ironically, they the dancers were celebrating a planned tourism development that could further erode a unique community with an already muffled political voice, dwindling numbers and vanishing culture. Blacks account for only 2 percent of the people in this nation of 7.4 million.

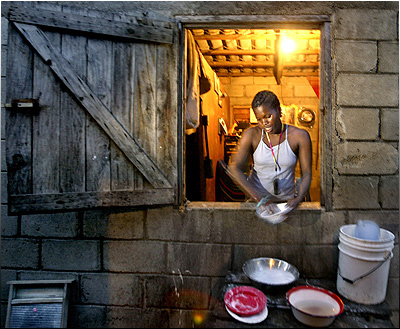

With virtually no economic clout, widespread poverty and voter apathy within their community, the Garífuna face a difficult challenge keeping their land.

"The investors and the government divided the [Garífuna] community through money; public opinion was bought," said Domingo Alvarez, 65, a senior official of the Fraternal Black Organization of Honduras. ‘‘Even as there are denunciations, others simply dance to the tune of the state."

TOURISM V. INVESTMENT

The Garífuna population in Honduras is officially estimated at 45,000, dispersed across more than 30 communities. They speak their own Africa-based language, Garífuna, as well as Spanish and English. But while their communities are promoted in Honduran tourism pamphlets, their numbers are too small to carry political weight.

"We are a minority, and even after 200 years of being here, we are still considered foreigners," Alvarez said.

Today, Garífuna communities can be found in small towns along Honduras' Caribbean coast, including one named Miami, a tiny slice of shoreline where families still live in straw huts.

But they are struggling to maintain their roots amid a dwindling population and several divisive issues -- the most contentious of them the swath of land where the war dance was performed held in October.

The site is being developed into an $11 million Micos Beach and Golf Resort. Land where about 35 Garífuna families had lived for generations was expropriated by the government to make room for the project.

During the groundbreaking ceremony, Honduran President Manuel Zelaya promised that about $3 million would be set aside to invest in moneymaking projects specifically for the Garífuna -- but the community remains skeptical.

"We live a little poor," said Isaac Arriola, 34, who was at the dance to celebrate the project. "I think we are going to get some work and get some money."

"Maybe we are going to clean or cook, but we won't have the top jobs," countered Climaco Martínez, 66. "We don't have the necessary training to do anything else, and the government won't invest in that."

Martínez's wife, Balbina, said that while the planned resort could provide jobs, she worries about its impact on Garífuna society.

"When I grew up over here, we were innocent," she said. "My grandmother never went to the doctor. She used herbs for ailments. There are hardly any herbs anymore."

TRADITIONAL BELIEFS

Those who still believe in herbal remedies infused with a dose of spirituality now turn to Félix Valerio, a respected curandero, or medicine man.

The rugged 70-year-old gets around on a rusty bicycle and is always barefoot "to feel the power."

"We are here to combat evil. We've saved a lot of souls," said Valerio, using the ‘‘we" to refer to himself and the spirits he prays to for guidance.

Consultations take place in the bedroom of a modest Caribbean-style home. One corner contains an altar topped with several statues, a portrait of Jesus, candles and flowers. Valerio listens to his clients' problems and seeks guidance from spirits to provide a solution.

Remedies consist of herbs combined with scented water that Valerio prepares in his tiny kitchen. People travel from all over the country to see him. Everyone leaves with a dose of advice and a bottle of herbal brew.

Valerio, whose grandfather settled in the region in 1890, has lived in the same house since he was born. The house faces the ocean -- a Garífuna trademark. "The Garífuna have never liked mountains," Valerio said. "They've always liked the ocean, fishing."

GOVERNMENT SERVICES

In the nearby fishing community of La Ensenada, Garífuna leader Gerardo Colón Rochez complained about a lack of government services as well as a loss of culture. "We have maintained our tradition, but we're also losing it," Colón said. "In part, it has to do with racism, but also partly due to us not mobilizing ourselves."

"Look, this is the most touristic community and we don't even have potable water," he said. "Before, we could take water from the ground and boil it. But now, there are latrines for the tourists, and the septic tanks have ruined the ground."

Garífuna artist Nicolás Colón Gutiérrez is trying to inspire youths by teaching them to paint.

"In the Garífuna community, a lot of talent is being lost," Colón he said. "This is the only ethnic group [in Honduras] that has maintained its language and culture."

"Not all of them can make it to the United States or be doctors or professionals," he said. "But they can make a living as talented artists. Here, the community migrates because the government offers nothing for its citizens. This program is providing a message of hope."

Hope also was at the core of a dance recital at a church in the community of San Juan, where a group of teenage girls held maracas over their heads, shaking them to the rhythm of drums played by a handful of boys.

That performance was not about war. It was about cultural survival -- practicing for a parade that would celebrate their heritage. They planned to dance down sandy streets, behind a banner with these Garífuna words: "Lema Ibagari lau Emenigini Wabaruaguon" -- "Life and hope are just ahead."

More information about the Garífuna: