Colombian Police Gen. Luis Moore says he swallowed hard when his fellow officers made offhand remarks that Afro-Colombians were lazy or not smart enough.

One of his colleagues even told him to his face that he didn't like black people.

But Moore, 47, who describes himself as a "positive person'' ploughed on. He became Colombia's first black general and is now its top highway police chief.

"This was not easy," Moore says. "There were moments when many others rejected this. There were some that said, ‘Why him and not me?' And others that tried to stop me, because they thought that blacks weren't as capable as them." Skin color makes for complicated identity in Latin America, where so many people carry mixes of African, European and indigenous blood. What's clear is that those with darker skins tend to be less educated and are paid less. They live in the poorest urban districts, and farm the least fertile lands.

But despite these odds, a small group has made it to the top. Their personal stories reveal just how they were shaped by their color, and how this fueled a determination to succeed. On the way, they faced humiliations, from a Brazilian entertainer mistaken for a valet attendant to an Argentine singer whose teacher ordered him to take off his afro ‘‘wig."

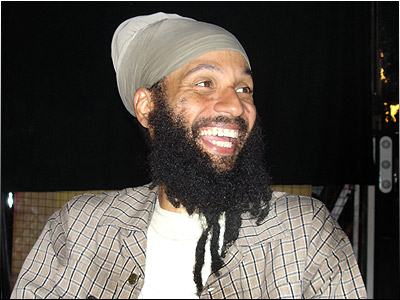

THE REGGAE ARTIST

BUENOS AIRES -- When musician Fidel Nadal chats with a fellow Argentine, he braces for the inevitable question: You're not from here, are you?

"That's always, always, always the first thing they ask me," he says.

The 42-year old Nadal is a fifth-generation Argentine. Yet most Argentines do not recognize Nadal as one of their own because he is black in a country that sees itself as almost exclusively European.

Nadal recalls being the only black student in his Buenos Aires elementary school in the 1960s. Some of his classmates nicknamed him Pelé -- after Brazil's greatest soccer star, who is black. Others called him Kunta -- after the main character in the TV miniseries Roots.

The less creative simply yelled Che, negro -- hey, black man.

By the age of 14, Nadal had grown an afro. On the first day of class, one of his teachers asked him -- in front of the class -- to stop kidding and take off his wig.

"That was probably the first time that I felt my racial identity," says Nadal.

"Calling my hair a wig was like asking an Asian man to open his eyes."

A music lover, he came across a record by reggae icon Bob Marley. And Marley led Nadal to Jamaica, the Rastafarian movement and his connection to Africa.

"I identified with Marley," he says, "because of his -- and my -- race but, above all, I identified with the rebel."

Today, he is recording his 15th record, Emocionado, and packing small clubs in Buenos Aires. Nadal may not be mainstream, but a small and enthusiastic audience follows him from his time as the frontman of Todos tus Muertos, a famous Argentine punk and reggae band whose lyrics had social and political content.

Asked if he feels he has become a stereotype in a country where black people only bring to mind music or sports, he pauses to consider his answer.

"You know, I fought against the prejudice, against the ignorance for years. And maybe yes, I have become a stereotype -- the black man with dreadlocks who plays reggae," he says. "But I don't care anymore. Today I can say, ‘I am African, and this is who I am'."

THE POLITICIAN

PANAMA CITY -- Epsy Campbell, whose grandparents moved to Costa Rica from Jamaica to work on the country's railroads, is an economist-turned activist-turned politician who came within 3,300 votes of becoming vice president of Costa Rica last year.

Outside the Caribbean, no Afro-descendant has ever reached such political heights in the hemisphere. She's even mentioned as a serious contender for the presidency in the next elections.

"I am the most atypical of the Costa Rican stereotype," she says, flashing a politician's easy smile. "I'm black, and I'm a woman."

For 42-year old Campbell, racism can be subtle.

"I can't say racism doesn't exist," she told The Miami Herald at a conference for black activists in Panama City, "but in a person like me it manifests in ways that are so sophisticated that many times it is hard to spot."

Occasionally, she notes expressions of surprise in people she meets, as if her intelligence and eloquence defy expectations. It's almost racism in reverse, she says, as though people are overcome with an "excess of admiration."

Campbell is a busy woman these days, heading the Citizens' Action Party -- a coalition of grassroots organizations that was created in 2002 and is now Costa Rica's second biggest party.

But she still finds time to address Latin American black activists, with speeches that are a mix of pep talk and hard facts.

There are few black judges in the region but many blacks in jail, she tells her audiences. Latin American blacks in positions of power -- cabinet posts and other senior government jobs -- number fewer than 20 and only 2 percent of all elected legislators are black.

The novelty of a black female face in Costa Rican politics is beginning to wear off, she said, and that's probably a good thing.

"You are no longer the exception, the rarity," she says. "Racism and discrimination have much to do with ignorance and fear of the unknown."

THE TV ENTERPRENEUR

RIO DE JANEIRO -- As a child, José de Paula Neto sold candy to support his poor family. After his mother died when he was 11, he raised his siblings alone.

Two decades later, after he become a successful singer and TV personality, he recalls crying after a white man at a fancy restaurant mistook him for a valet attendant and handed him a set of car keys.

"I couldn't hold it back," he says.

De Paula has turned that pain into a lifelong fight against what he sees as a society rigged against Afro-Brazilians. The 36-year-old has been one of Brazil's few black celebrities to speak out on race issues.

In 2005, he launched TV da Gente, or Our TV, Brazil's first channel targeting black viewers. The station is now struggling to survive, but de Paula says it is needed in a country that is half black but appears almost completely white on television.

"The networks put an (black) actor there, another one there and say that everything's fine," he said. "Their tactic is to give visibility to a few while forcing invisibility on millions."

His many critics have accused him of aggravating the country's racial divisions by focusing on black audiences. The row over TV da Gente may have cost de Paula his long-running variety show on the Record network, cancelled last summer.

De Paula sank millions of his own dollars and brought in Angolan investors. Regulators wouldn't give the channel space on the airwaves and cable providers wouldn't carry it. To save money de Paula moved production in January from the southern business center of Sao Paulo to the predominantly black city of Salvador in northeastern Brazil.

De Paula said he's not giving up.

"I didn't stop being black because I got some money," he said. "My struggle is very serious. It's a commitment to my people."

THE BEAUTY QUEEN

GUATEMALA CITY -- Marva Weatherborn's father died when she was 11 but she remembers his advice: ‘Never let anyone make you feel like you are less. We all have the same rights."

In 2004 Weatherborn became Miss Guatemala, the first and still only black woman to win the pageant in a nation where dark skin is not always embraced.

"Color," she said, "is automatically associated with inferiority."

Weatherborn's success brought a pleasant face and voice to Afro-descendants in Guatemala, who make up less than 1 percent of the country's 12.7 million people. They have no political representation, no organized movement, no prominent community leaders.

But their status changed, at least a little, after Weatherborn's win.

Until she was crowned, she was left out of beauty pageant posters with other contestants.

"When she won, it reinforced the idea that minorities can also have opportunities," said Tony Berganza, a beauty industry veteran and owner of a modeling agency that represented Weatherborn.

The youngest of three sisters, Weatherborn, 24, grew up in Puerto Barrios, a small port town on the Caribbean coast. Most residents there are Afro-Guatemalans, Caribbean immigrants and indigenous Mayans.

When she won the beauty pageant, she came to be known as the Barbie Negra.

"It doesn't bother me to be called black, but it depends on how it's used," Weatherborn said. "I'm a happy black person."

After winning the title, she got a job at the Institute of Tourism and studied international relations. A serious car crash last summer derailed her plans but she hopes to resume her studies soon and one day work for an organization that helps Afro-descendants and others.

"Equality is a long way off here," she said. "I want to help people and, my race, obviously. Now, because people know who I am, I'm treated as an equal."

THE POLICE CHIEF

CALI -- In many ways, Colombia's Gen. Luis Moore was fortunate.

According to government data, 80 percent of Afro-Colombians live under the poverty line, many of them in rural areas where the country's long-running civil war has forced many to flee, join or perish.

Moore grew up in a mostly white, middle class community along the Caribbean coast. His mother was a lawyer and the first female governor of the northern Choco province, and his father was a physics and math teacher.

It was his parents who imbued him with his sense of purpose, honor and respect, he says. "You're not more than anyone, you're not less than anyone," they would tell him. Moore joined the police force in 1975 and became part of the first group of officers to fly helicopters for Colombia's armed forces in the early 1980s.

Along the way, Moore became el negro Moore, a term that he acknowledged could be used in a harsh or kind way.

"Colombia is a country of contrasts," Moore said. "We have a little of everything. But there are some who think they're totally pure and so they see the others as impure. They don't see themselves as part of this mestizaje.

"And although some say, ‘No, I'm not racist' -- when they have to decide who should fill a position or do a job, they say, ‘Well, I prefer the white guy over the black guy."

Moore felt the stigma of race in his personal life as well, especially when he began dating Graciela Díaz, a white woman from a small, conservative city in the central Andean range.

"A lot of people saw it negatively," he said. "Others didn't care."

Díaz said she never thought about it. For her, he was a gentleman and after 22 years, still is.

"He has more culture than any white, blonde, or blue person that I've ever known," she said. "He still opens the car door for me."